On Sunday, 13 October, Poland went to the polls. These were the first parliamentary elections since 2015, when the Law & Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) party was brought to power with the first single-party parliamentary majority since the transition from socialism. A frenetic socio-political environment, marked by recurrent sparks of political controversy, characterised the PiS government from 2015 to 2019. And Polish voters returned that government to power.

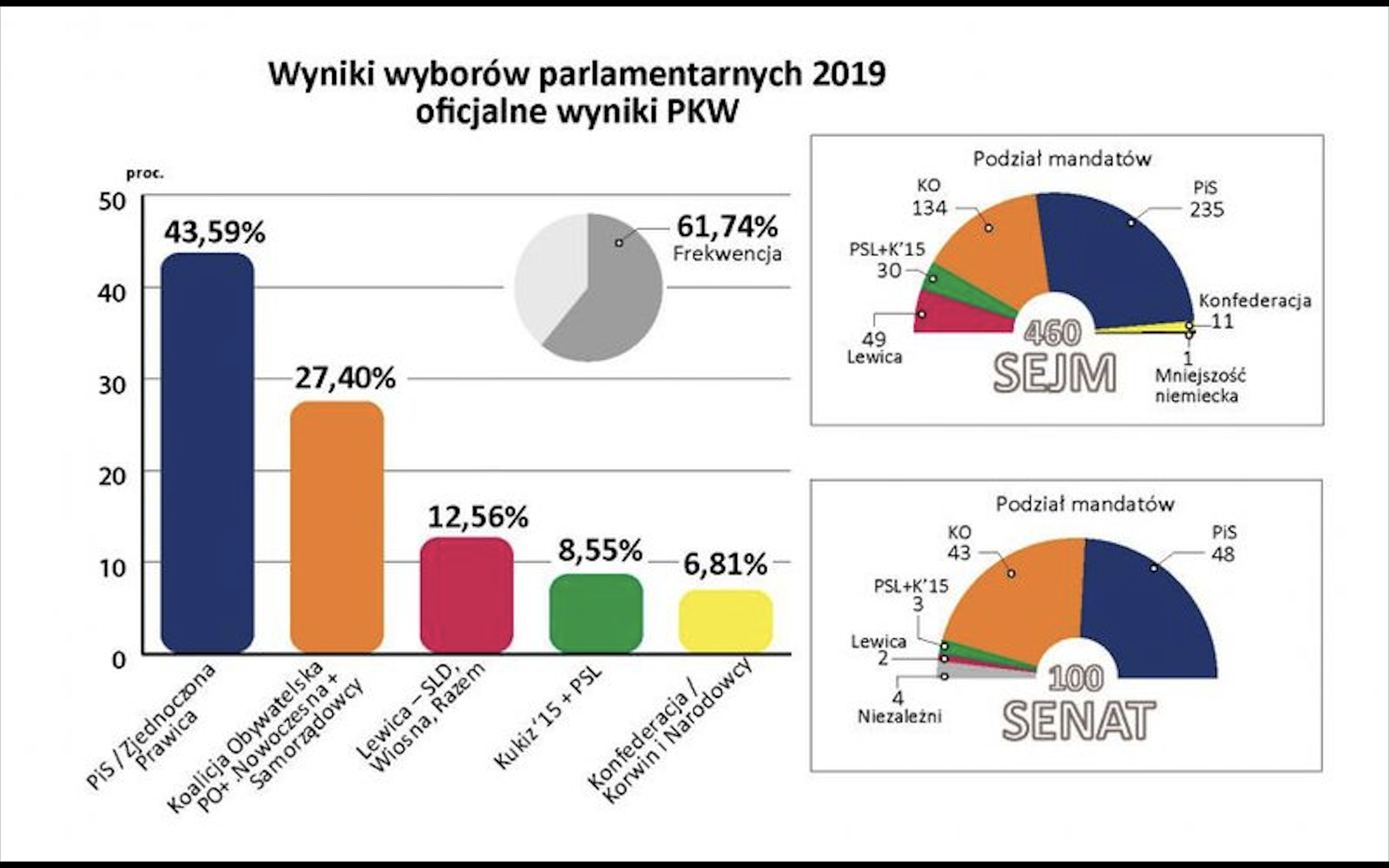

Analysis of the Polish elections and forecasts of what is to come must maintain an essential fact: the PiS party retains governing authority and has been given little cause to alter its political demeanour. But this election did not go according to PiS’s plan. Despite strong economic growth (over 5 per cent in 2018), steadily declining unemployment (from 8 per cent in 2015 to just over 3 per cent currently), and both popular and economically advantageous welfare policies (most notably, 500+), PiS barely retained its majority in the Sejm (the lower house of parliament) and lost its majority in the Senate (the upper house). Among other implications, this puzzling result suggests three conclusions about the recent past and short-term future of politics in Poland.

First, there was a massive rise in voter turnout at these elections. More than three million more voters participated in 2019 than in 2015, representing nearly 62 per cent of the population compared with just over 50 per cent in 2015. PiS won a greater number of votes, but so too did the main opposition, Civic Coalition (Koalicja Obywatelska, KO), as well as the Left (Lewica) party and the far-right Confederation Liberty & Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość, or simply ‘Konfederacja’) party. This rising tide of participation supports the view that the policies and rhetoric of PiS, sometimes strident and polarising, have mobilised previously disengaged citizens—but on both sides of the ideological divide. Along with the new voters that support the generally populist, nationalist, and conservative policies of PiS, there is growing demand for Konfederacja’s starker populist and nationalist positions. (Konfederacja received a disproportionate share of votes from young men.) At the same time, the return of Lewica to parliament is arguably symptomatic of the considerable social mobilisation against the conservative and authoritarian initiatives of PiS over the last few years.

Second, as a result of the greater ideological diversity represented in Poland’s parliament, the everyday conduct of politics may become less polarised. Whereas the previous legislative period was characterised by the contrast between the conservative nationalist rhetoric of PiS and the relative moderation of KO, the new period will surely witness a greater pluralism of voices among parliamentarians. The specific effect on the government’s rhetoric is not yet clear: the surge in support for Konfederacja may cause PiS to worry about its electoral flank, but the presence of Lewica and some representatives of KO gives a parliamentary presence to the thousands of demonstrators and disgruntled Poles that opposed PiS action and rhetoric on refugee, LGBT, and judiciary issues over the last four years.

Third, this election solidifies one particularly salient policy development: the broad-based acceptance of the ‘500+’ welfare scheme. The programme, introduced over three years ago, provides 500 Polish złoty (approximately 115 Euros) per child (after the first child), per month. Initially lambasted by opposition politicians as fiscally irresponsible and an unabashed attempt to buy political support, 500+ is now virtually sacrosanct. Apart from alleviating financial burdens and providing spare disposable income—resultant rises in spending on goods and services has undoubtedly contributed to Poland’s economic growth—recipients of 500+ benefits often speak of the novel experience of not being stigmatised by receiving welfare. The scheme’s popularity and evident economic advantages compelled nearly all of the parties to pledge to maintain it.

The returned PiS government may meet greater institutional resistance to its agenda, particularly from the Senate, but it can plausibly assert that it has a clear mandate to continue its political programme. That means that the PiS actions, both unifying policies, like 500+, and divisive initiatives, like alteration of the judiciary and demonisation of ‘LGBT ideology,’ will likely continue apace. The 2020 Presidential election will be the first indicator of how the Polish electorate is responding to the work of the second PiS government.

Originally published as a blog by Open Democracy: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/global-extremes/whither-poland-after-2019-parliamentary-elections/.